Often mentioned in hushed tones, the mysterious process of shattering silk is one of the major issues that you’re likely to come across during your adventures in vintage and antique fashions.

It’s a rather misunderstood issue and will often be used as a generic term for fabric that is falling apart, forming rips or holes or turning to dust in your hands. Deterioration might indicate shattering or it could be dry rot or iron mordant that is eating your beloved dress.

Better quality silks are heavier and so historically silk was sold by weight. Some manufacturers introduced metallic salts into the process to make it heavier, and receive a higher price. Additionally, adding the salts (which usually contained iron or tin) created a fabric with a pleasing rustling noise, for example silk taffetas and satins. These were particularly popular during the 19th century in ladies eveningwear, but also mens accessories like bow ties and cravats.

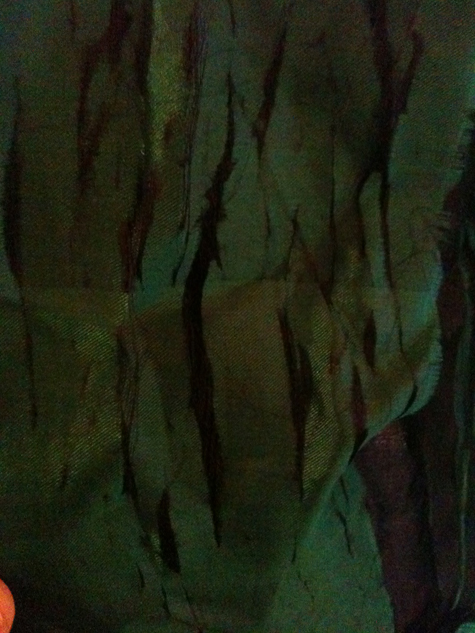

Over time, the salts damage the fabric, producing small tears that become big tears. The effect is rather as if someone has taken a razor to the garment. Here’s a stunning capelet from the 1890s that was sold in the recent National Trust vintage clothing sale.

Please excuse the less than ideal iphone pics.

In this case, the shattering process is well underway and has affected most of the fabric – creating a striking effect that almost looks like a design feature. When a large amount of shattering is present, it can be quite beautiful.

This capelet is made of shot silk, where the warp threads are black and the weft are green, producing a rich two-tone effect. The black appears in the shattered rips – it almost looks like ribbons.

The garment in this case, is quite wearable although continued wear and exposure to light will increase the deterioration until it’s completely shredded. The black panels are made of a different fabric, so are not affected. I really like the look, although we’re looking at advanced decay.

Victorian and Edwardian garments are the most affected but there are many 20th century fashions that are also afflicted: the most recent that I’ve seen was an evening gown with red roses printed on black from about 1957 – stunning dress, but a heart-breaker.

Shattering generally appears along the weave, so the rips will appear mostly in the same direction – or where the fabric has been folded due to the stress placed on the fabric. Mostly they will be random, and that’s one of the give-aways: dry rot and iron mordant affect certain areas, but shattering is indiscriminate.

There is no way to stop the shattering process, so it’s best to avoid acquiring an afflicted garment unless your plans are for a short term use or like me, you love the fragile beauty of it.

Of course, if you happen to have in your collection something fabulous like a 1939 Balenciaga “Infanta” gown, like the National Gallery of Victoria – you will do your best to restore it.

Backing the delicate textile onto a material can strengthen the fabric and controlling light and stress will help too. For professional textile restorers there are a range of products available.

Here is a photo of the NGV’s gown – reproduced with thanks. No damage is visible so it’s likely to be slight, which is very good news. I do hope that one day we can see it on display. It’s silk satin trimmed in velvet.

This post is part of the Vintage 101 series – you can see more posts in the series here.

Discover more from Circa Vintage Clothing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

That last dress is just gorgeous….would be amazing to see in real life 🙂

Hi Nicole,I bought one of your books a number of years ago and was delighted to get your updates via Sylvia Walsh from RMIT today. I have a collection of victoriana and edwardian pieces plus textiles & clothing from the last century. some on display at my shop some in my private museum at home and other bits and pieces ready to be shared with others.

would love to make contact with you and chat more.

kind regards

Gracie matthews

Hi Gracie, lovely to meet you: you’re welcome to come and visit my shop some time or we can tee something up after I’ve finished my current book. All the best – Nicole

Im enjoying this site very much. Re shattering..or dry rot, as I have just learned about… I notice some of my afflicted 19th century garments do seem terrifically dry, dry as parchment. Stupid question….is there such a thing as rehydrating textiles?? would laying the fabric down on the bed and lightly spraying it with water and then letting it dry do anything to add a normal humidity to the garment and replace flexibility? just curious.

A good question and one I’m sure that textile conservators could answer. My feeling is “probably unlikely” because it’s the structure of the textile that has been damaged, with whatever environmental factor that’s impacting it (humidity, changes in temperature, mould or mildew, insects etc). I’d love to go and study these things, and learn about the chemistry of it all. It’s a fascinating area.